Hilary – Running Through the Storm

I was training for my 7th marathon in 2023 when I found out my stage IV cancer had spread again, this time to my brain. I found my brain mets by accident when they showed up on an unrelated MRI of my cervical spine. I had no symptoms and would not have known to ask for diagnostic testing. Given I had over 30 tumors in that first scan, I was surprised that I was not experiencing any side effects. I often think about why that was the case. Did it have anything to do with my lifestyle? Or was I experiencing side effects that I hadn’t even clocked?

With hindsight it is possible that the tumors were affecting my balance. I run almost every day and I found myself tripping and falling much more frequently. But, except for the trips and falls, running has helped me immensely through my battle with brain mets. As counterintuitive as it seems, exercise helps combat fatigue and fatigue is probably one of the most pervasive side effects of cancer and related treatments. I am currently on my third line treatment which is Enhertu. Enhertu has been great for shrinking my brain mets, but, at the same time it has caused me incredible fatigue. I truly feel that pushing myself out the door for a short run has helped me to manage and push back against my fatigue. According to the American Cancer Society, exercise may improve physical function, decrease fatigue, and improve quality of life.

I also believe that exercise of any kind makes our bodies stronger and more capable of fighting cancer and managing all other side effects of treatment. Strength training can build bone density and slow bone loss, side effects that we often experience due to hormone suppression treatments. I also feel much more in tune with my body. When my iron levels dropped dramatically, I was able to tell immediately that something was wrong when I tried to go for a run and couldn’t do so without getting lightheaded.

Running also gives me a sense of control over my own body. Cancer sucks! It feels like your whole life has been turned upside down. Your schedule is dictated by constant doctor’s visits, infusions, blood work, and diagnostic scans. It’s a small thing but being able to decide when and how I move my body gives me a small sense of control in this journey filled with uncertainty. I use runs to decompress after a stressful doctor’s appointment and I use runs to celebrate after a good scan. I run before each chemo infusion because it helps me walk into the infusion center with a sense of pride and accomplishment, ready to face the day. I have also made so many great friends through exercise and I am so grateful for the support that comes from going on a walk or a run with a friend.

Research shows that moving your body can contribute to happiness. Physical activity can release endorphins, serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin (four hormones all associated with different aspects of happiness). The so-called “runner’s high” is probably the result of the release of endorphins or perhaps of endocannabinoids (a naturally produced substance similar to cannabis). In the “Happiness Project” by Gretchen Rubin the author posits that a sense of growth and achievement is also a key factor in obtaining happiness. Setting running goals for myself and pushing through exercise when I am not feeling my best gives me a sense of accomplishment and pride more than any of my antidepressants! Since my MBC progressed to my brain I have set numerous exercise goals for myself. I have run 3 marathons (most recently, the London Marathon in April of 2025) and increased the maximum that I can lift in several weightlifting exercises. I also eat healthier because I want to fuel my body properly for exercise.

My advice to others is to start small. Of course, talk to your care team first to make sure the form of exercise you are interested in pursuing is safe. Once you have been cleared, start with a 10 minute walk or some gentle yoga. Always start and end with a warm up and cool down, which should include some light stretching. As the weather starts to get nice, take advantage of the increased daylight hours to get outside and move your body. You will thank yourself later for this little bit of self care!

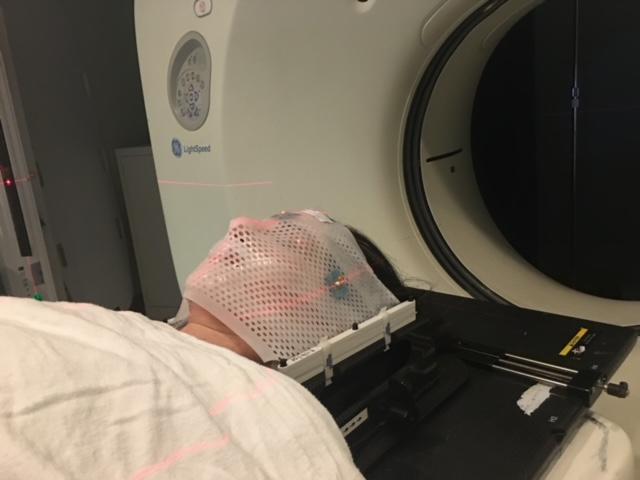

Getting the mask made was no picnic. I felt it hard to breathe and swallow and couldn’t wait to get it off.I got used to it pretty fast, which is lucky for me since I’ve used it multiple times since that first time. This is a picture of me right before my first SRS radiation. I was nervous about the side effects, but otherwise, I was comfortable and okay with the mask. I can imagine that claustrophobic people may have a hard time getting used to this.

Getting the mask made was no picnic. I felt it hard to breathe and swallow and couldn’t wait to get it off.I got used to it pretty fast, which is lucky for me since I’ve used it multiple times since that first time. This is a picture of me right before my first SRS radiation. I was nervous about the side effects, but otherwise, I was comfortable and okay with the mask. I can imagine that claustrophobic people may have a hard time getting used to this.