Dr. Ayal Aizer is a radiation oncologist in Boston, MA at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Radiation Oncology Overview

Types of Radiation to Treat Brain Mets

Side Effects & Risks of Radiation

What to Expect after Radiation

Clinical Trials & Emerging Research

Dr. Aizer is an Assistant Professor of Radiation Oncology at Harvard Medical School who serves as the Director of Central Nervous System Radiation Oncology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital / Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, MA.

He completed medical school at Yale School of Medicine in 2009 before pursuing radiation oncology residency at the Harvard Radiation Oncology Program, which he completed in 2014. Dr. Aizer specializes in the management of brain metastases and his research efforts seek to improve outcomes in this population. He leads several prospective clinical trials involving patients with brain metastases and has published both retrospective and large data-based studies centered on the management of patients with this condition.

Full Transcript

Dr. Ayal Aizer (Parts 1-5)

Lianne Kraemer:

Welcome to those who are joining us today. I am patient advocate, Lianne Kraemer, and we’re going to be doing an interview with Dr. Ayal Aizer. He is the assistant professor of radiation oncology at Harvard Medical School who serves as the Director of the Central Nervous System, Radiation Oncology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

He completed medical school at Yale School of Medicine in 2009 before pursuing radiation oncology residency at the Harvard Radiation Oncology Program, which he completed in 2014. Dr. Aizer focuses his clinical research efforts on the management of brain metastasis. He leads several prospective clinical trials involving patients with brain metastasis and he published both retrospective and large database studies centered on the management of patients with this condition. His career is devoted to improving the understanding of management and outcomes in patients with brain metastasis.

Thank you for joining us, Dr. Aizer, it is an absolute pleasure to have you here with us today.

Dr. Aizer:

Thank you, Lianne, that was a lovely introduction – and it’s funny that we’re talking more formally than we have been known to do. –

Lianne Kraemer:

I know. And for those watching Dr. Aizer is actually my radiation oncologist and just on a personal note, he is a truly wonderful human and radiation oncologist. And, just, you know, a wealth of knowledge. And I always think you’re so special because it’s such a niche area that you work in that not only do you specialize in brain, but you specialize in brain metastasis. So it’s kind of like this niche within the niche, at least that’s how I look at it.

So why don’t you start by telling us what you do as a radiation oncologist?

Dr. Aizer:

Well, just to respond very briefly, I would say that it’s our relationship and that definitely goes both ways. And of course, a privilege and honor to interact with you in any way, shape or form that we have the opportunity to do so.

So to answer your first question about what our radiation oncologist does – so radiation oncologists train relatively broadly in oncology. The training program is typically about four years in life. And we actually rotate through all of the relevant disease sites. And that can be helpful with giving us a background, not only in radiation, but also in oncology in general.

And I think when it comes to the brain, one thing that is nice from a radiation standpoint, is the ability to try to put everything together as best routine: the radiation to drug therapy, the surgical therapy, as well as the supportive care and quality of life issues. Not to say that we’re an expert in all of those things, many ways, far from it, at times, but it’s nice to be able to try to counsel patients from an oncology standpoint, not just purely on a radiation standpoint.

So ultimately the treatment we provide is radiation to patients with brain tumors. However, a lot goes into the question of, should we radiate, in addition to how we radiate. So typically, you know, every radiation oncologist will be different, but the brain, it’s definitely a site where we try to bring it all together.

Lianne Kraemer:

So when do you become involved in a patient’s care? As far as, when a patient is diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, that is, you know, spread to the brain. So how do you become involved in their care?

Dr. Aizer:

It’s a great question. So typically we’ll get a referral from either a neurosurgeon, if there was a consideration regarding surgical therapy as a first step, or a medical oncologist, or a palliative care physician.

So one of the patient’s team members will often reach out to us and ask us to take a look at the case and weigh in on radiation and other elements of management. So we typically look at a referral from one of those sources and that includes inpatient performance as well.

Lianne Kraemer:

So it sounds like it’s really important too, that if you’re getting a referral, if how you typically start with a patient is through a referral from a surgeon or an oncologist, that the importance exists to work really as a team, than with those professions.

Dr. Aizer:

That’s a great point, Lianne. So, increasingly, radiation is just one component of therapy and a team effort is really integral. So, whether that’s multiple doctors in the same room with a patient, or multiple independent visits where the doctors are talking behind the scenes, I completely agree that, you know, optimal management is really multidisciplinary in nature, spanning medical oncologists, neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, palliative care physicians, and other doctors as well.

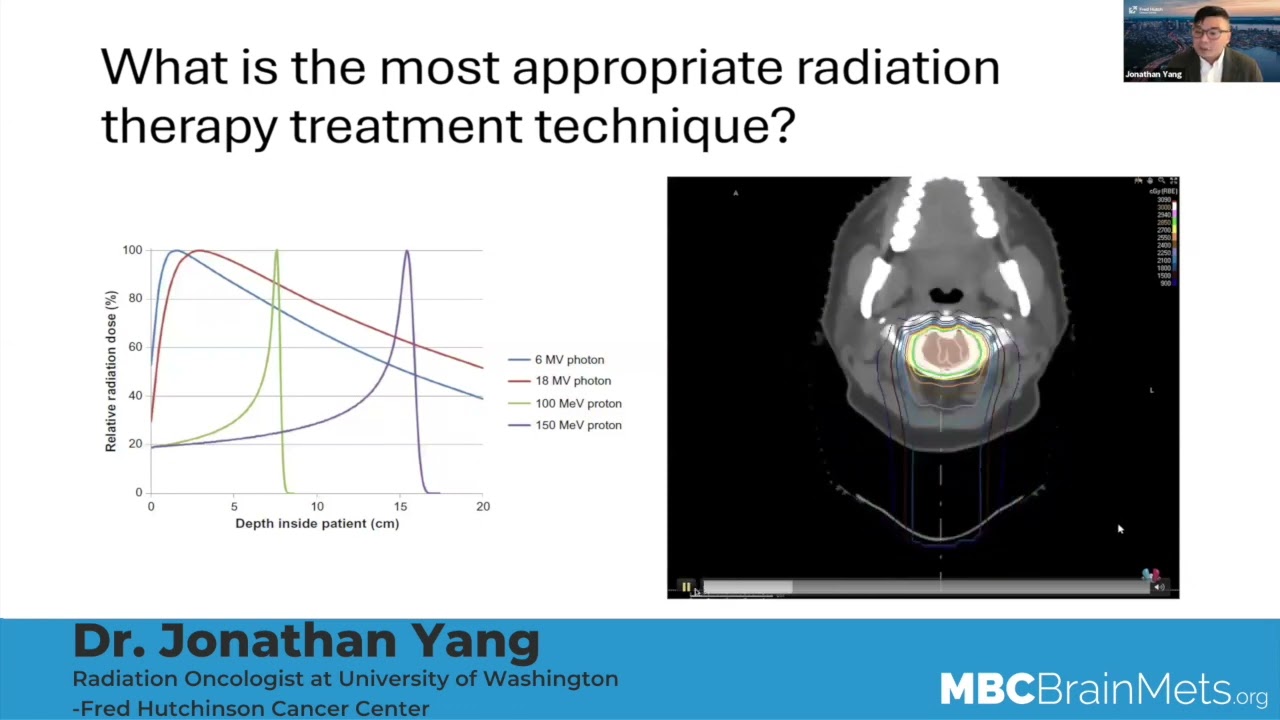

Video #2 – Types of Radiation to Treat Brain Mets

Lianne Kraemer:

So when we hear the discussion of radiation to the brain, we hear two terms, mainly, we will see the abbreviation, SRS or HBR. Can you talk to what SRS is? Especially the different machines that are used. We hear people talking about CyberKnife and Gamma Knife and just a brief kind of explanation of what that is.

Dr. Aizer:

Sure. It’s a great question. So SRS stands for stereotactic radiosurgery. What that means, essentially, is that there’s focused radiation being administered to one, or more, parts of the brain, but it’s targeted to a specific area, rather than encompassing the entire brain, for example.

The nomenclature can be confusing because, you know, SRS is typically thought of as radiation given in a single day to the brain, but that radiation can be delivered in multiple days, when a single day is just not safe or viable. And a number of names exist for that; some people call that fractionated SRS. Some people will call that SBRT, or stereotactic body radiation therapy. Some people will call that SRT or stereotactic radiotherapy. But all of those refer to focused radiation given over more than one day, still to a limited number of targets, typically.

In terms of how the radiation is actually done, the specific technology – you allude to a great point. So there’s, you know, multiple different technologies used to administer SRS or SRT, for example. There’s Gamma Knife, there’s CyberKnife, there’s linear accelerator-based SRS. There are new modalities, like ZAP. But ultimately one of the most important elements is not the technology that’s chosen, especially for this reason, but rather, that a team that’s instilled in the delivery of radiation is overseeing the care. Because it’s more than just which technology has been selected – those differences tend to be relatively subtle. Some of the randomized data has told us that, for example, including an Italian randomized study that compared Gamma Knife versus a new accelerator-based treatment with really very little difference.

But, I think one thing we all would agree on is that you want to go to a center that has experience, that the given patient feels comfortable in not only with the doctors, but also the nurses and therapists and other people who are involved in the care of that patient. And not just say that we’re selecting one specific technological modality.

So I think it’s like driving a car, you know, there’s Toyota or Honda or Buick. And they’re all fine cars. But what probably makes the biggest difference on the road is who’s the driver or drivers of that car. So that’s how it looks.

Lianne Kraemer:

That’s a really, really great analogy. I think in discussing radiation with other patients, sometimes the focus really can be on which machine or which modality of radiation is best – should I get CyberKnife or should I have them do Gamma Knife. And what I’m hearing you say is it really doesn’t matter so much which one is used, more or so that you’re comfortable with the team that is going to be utilizing that form of radiation to treat your brain metastasis.

Dr. Aizer:

That’s well-stated. I completely agree.

Lianne Kraemer:

Really, and that’s really interesting. So what about whole brain radiation? Can you talk a little bit about that? How is that different from SRS?

Dr. Aizer:

Sure. So with whole brain radiation, now, the radiation encompasses the entirety of the brain. So rather than treating individual tumors in the brain, the radiation covers the entirety of the brain. That includes the tumors that are seen on the scan, that also will include microscopic areas of disease. So microscopic tumors, meaning tumors that are so small that you can’t even really see them on the scan. And the radiation encompasses everything. And while that sounds good, in some respects, it also has some unique toxicities which have to be balanced, and I’m sure we’re going to get into that later. But rather than a focused administration of radiation, now we’re treating the entirety of the brain and I’m sure we’ll get into this later. There are some spinoffs of that treatment that may allow certain areas to be excluded, but ultimately the entirety of the brain is being targeted.

It’s typically a treatment that’s given, not in one day, but between one and three weeks. When people do larger numbers of treatments the dose per day typically falls. So it’s roughly equivalent, whether it’s one week, two weeks, three weeks, it’s really up to the patient and the radiation team to work that out. And also other factors that go into that – how quickly does the patient need to get back to drug therapy, among other individual considerations. But yes, it’s typically a longer treatment and, of course, treating the entire brain rather than individual brain tumors.

Lianne Kraemer:

So when you’re talking about whole-brain radiation, a term you’ll hear is hippocampal avoidance or hippocampal sparing. How does that fit into what you’re discussing?

Dr. Aizer:

Sure. Very great question, Lianne. So I can share this screen and sometimes a visual is helpful. You asked appropriately about hippocampal sparing in whole brain radiation and what that treatment is, is that the entire brain is treated with radiation with the exception of the hippocampi, and that’s the plural for the hippocampus. There’s one hippocampus on the right. We also look at imaging backwards. So you’ll see the mouse clicker on the left side, but we’re actually referring to the right.

So there’s one hippocampus on the right, and there’s one hippocampus on the left. And what you’re looking at here is the right and left hippocampus. You’re looking at an MRI in the top row, a CT in the bottom wall, you’re looking at different views. So the left is sort of a horizontal cut and the center and right are up and down cuts of different pictures.

And what you’re seeing is that the radiation dose, which is this kind of shaded cloud, doesn’t include the hippocampus. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t get any radiation, it just gets a much lower dose of radiation than the rest of the brain does. And the reason that this is considered is because one of the most significant side effects of whole brain radiation is cognitive problems after treatment. And sparing the hippocampus can preserve cognitive function among such patients.

This was proven relatively definitively in a randomized trial, published by Paul Brown and colleagues a little over a year and a half ago. And what they did was they took patients who needed whole brain radiation and they were randomized to receive either conventional whole brain radiation, where the hippocampus is included in the radiation field. Or hippocampal sparing radiation, where it’s excluded.

And what they found was that there was better cognition and better memory, better thinking in the group that had hippocampal sparing radiation. And it’s important to also note that everyone on both the control arm and the hippocampal sparing arm … and that’s another way to preserve cognitive function. And that was proven back in a 2013 study to get benefit.

So in patients who are candidates for hippocampus sparing whole brain radiation, it’s advantageous to use it. Now, the question comes about who is a candidate. So candidates are typically patients who don’t have tumors in or near the hippocampus. They’re being defined as typically five millimeters or less, As well as patients who don’t have leptomeningeal disease, and patients who can wait at least a few days before starting radiation, because regular whole brain radiation can be started typically in a few hours or a day. But hippocampal sparing, because it’s more complicated, typically takes longer. So if there’s an urgent need to use radiation, hippocampal sparing probably isn’t appropriate.

But assuming those criteria and a few other rare ones are met, hippocampal sparing is a more advantageous way to get over radiation than the historical way, which is conventional hippocampal radiation.

Lianne Kraemer:

And so you were talking about the reason for avoiding the hippocampus for memory and cognition. And that made me think of a drug that’s often paired with whole brain radiation. I’m not exactly sure how you pronounce it. I think it’s Memantine? Is that correct?

Dr. Aizer:

That is right.

Lianne Kraemer:

Can you talk a little bit to that?

Dr. Aizer:

Absolutely, so, Memantine is a drug which is thought to help cognition, meaning thinking and memory, in patients who have problems in those domains who may not even have cancer. So that’s where that drug started. And then about a decade ago, someone had the good idea of looking at that drug in patients with brain metastasis who are getting whole brain radiation.

So a randomized study was published by Paul Brown in 2013, looking at whole brain radiation with, or without Memantine. And the way that Memantine worked was they gave it in increasing doses over a few weeks, and then kept people on it for about six months. And what they found is that, in general, the Memantine group had better memory function and cognitive function.

People have spliced and diced this in different ways, but the main take-home message was that Memantine probably helps with thinking, memory, attention and other measures of cognitive function, after whole brain radiation.

The obvious next question is, well, what are the side effects? They didn’t see any bad side effects when they compared Memantine to placebo in that study. Lower grade side effects is less clear, but there don’t appear to be any significant side effects for the vast majority of patients.

Lianne Kraemer:

So, are you able to use whole brain radiation more than one time?

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah, it’s a great question and it does come up a lot. So really we want to try to avoid as best as possible repeat whole brain radiation. Because whole brain radiation given the first time can really have a lot of side effects. And then the idea of giving it the second time can be a lot for patients to tolerate. If it’s absolutely necessary, it is an option. We have occasionally resorted to it.

But there’s a number of things to factor in. One is that when you give whole brain radiation a second time, you’re often using a lower dose. So if tumors that were there at the time of first whole brain radiation have grown through that radiation, giving whole brain radiation a second time, maybe less optimal because they’re often using a lower dose for a tumor that’s often more aggressive.

In addition, the toxicities can really be quite significant. More and more and more, rather than consider that treatment, we either maximize focused radiation or stereotactic radiation. We typically will really push the envelope with that because we want to avoid repeatable brain radiation. Or increasingly in oncology there’s drugs that have, you know, some degree of efficacy in the brain. Then we try to really max out those drugs before resorting to another intense form of radiation. So this is an area that really needs more investigation. We don’t know what’s best, but we’re really shying away from using whole brain radiation as best we can.

Lianne Kraemer:

So, uh, you’re looking at using – let’s say you’ve had a patient who has had whole brain radiation and they are present with more lesions and you are looking more so at doing SRS again, rather than full brain radiation or does it just depend on the patient’s needs.

Dr. Aizer:

Increasingly, we’re using SRS as much as we can.

Lianne Kraemer:

Okay.

Dr. Aizer:

There’s a couple of rationales for it. SRS carries more radiation dose than does whole brain. So, although it’s given over a smaller number of days, biologically, it’s a stronger amount of radiation. So we’ve tried to utilize that a lot more without real upper limits in terms of the numbers that we’re going to treat.

If there are a hundred tumors, it just isn’t possible. But, you know, we’ve certainly had cases where, you know, you’re down 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 tumors, if need be. And we utilize that most often if it’s a tumor that was there at the time of whole brain and it grew through the whole brain. And the patient just doesn’t have drug options to even attempt at that point. And they still want to pursue aggressive care after they talk with their families, nurses, doctors, other people who are involved in their care.

Lianne Kraemer:

So you were mentioning just about the number of tumors that you can, you know, radiate the second time. What about radiating, making a decision between SRS and whole brain radiation – like the very first time a patient is referred to you, the number of lesions – how does that factor in your decision-making between SRS or using whole brain radiation?

Dr. Aizer:

It’s a great question. And most of the guidelines have focused on patients with a “limited” number of brain tumors versus a non-limited number of brain tumors and what’s appropriate.

I think we should be clear that all of the data, until very recently, has focused on patients with four tumors or less. By “all of the data,” I mean the highest quality of data, which are the randomized studies. So there’s been a multitude of randomized studies that have asked the question: “Can we use local therapy, like SRS, instead of whole brain radiation?” Meaning, can we omit whole brain radiation. And the answer to that question was largely, yes. As long as there’s a limited number of tumors.

Very recently, there was a study published in abstract form at the time of this recording, that went up to 15 brain tumors. But that was a study out of MD Anderson. There were a smaller number of patients included. We’re all eagerly awaiting that publication. And there are some ongoing trials that will test the question of how many metastases should we be thinking about with regard to SRS versus whole brain? I would add that it’s not just a number. It’s what drug options are there? How quickly are they developing? Is this someone who had no metastases a month ago and now has 15? Is it someone who’s always had 15, for the last year. You know, these are other factors to consider when weighing which treatment is most helpful.

Lianne Kraemer:

So we spoke a little bit about the number of lesions that help you to decide what’s the best as far as whole brain versus SRS. What about looking at a lesion, say you’ve been referred a patient from a medical oncologist and looking at them and deciding whether radiation is best or whether they need to be sent maybe to a neurosurgeon for surgery rather than radiation.

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah. That’s another point that comes up a lot, Lianne. So I’m glad you asked about that.

You know, it’s obviously important to have a multidisciplinary discussion about all options. And I think, we want to include the surgical team on all of these decisions about who should be going to the operating room – who might be able to – who could we get away with radiation with or who might not need either, just drug therapy, for example.

But, classically, the patients that we’ve considered referring to neurosurgery or who really would benefit from it, concretely – would be patients where there’s diagnostic uncertainty in the brain, meaning, like, you don’t know what is in the brain. We see something, we’re not sure what it is, it’s of a significant size, and we’re not super thrilled about watching it.

Because sometimes we see these little small areas in the brain and just end up watching. But if there’s something like two and a half centimeters in size, we think it could be an abscess or it could be a brain met. You know, that’s the type of patient that really needs to see a neurosurgeon, and quickly.

In addition to those patients, among patients who we strongly suspect have brain metastasis – if patients are having neurologic symptoms, especially if steroids are not helpful or helpful enough, those patients should almost always see a surgeon because surgery is by far the best therapy to make symptoms go away quickly. And that can be important for the future quality of life.

In addition, if there’s a patient who has a tumor that’s faulty,we pretty much refer all of those patients for a surgical evaluation because the likelihood of getting control with radiation is much lower. And often there’s not a long leash to try a drug out, because if there’s swelling around that piece of the tumor, that patient could quickly get a lot of symptoms, and we don’t want them to have that. So, we often will refer those patients to surgeons as well.

And then lastly, you know, if you look at the group of patients that have just one brain tumor, and there’s nothing in the body, we see this occasionally in breast cancer, it happens more in lung cancer. Sometimes even if it’s just one centimeter in size, we’ll refer to a surgeon, even if they’re having no symptoms because we kind of have wonder – I say wonder because the data supporting this is relatively weak – whether taking that tumor out, radiating the cavity after, is more beneficial to the patient long-term than just doing radiation by itself. So that’s another softer reason that we would refer them to a surgeon.

Lianne Kraemer:

So you just mentioned about radiating the tumor bed afterwards. Can you speak a little bit more to that? Because even when you refer for surgery, it seems that you are often involved in one way or another, even when they are surgically removed.

Dr. Aizer:

That’s a great point. So, you know, there’s two factors to consider when someone has had surgery to remove a brain tumor, you know, a brain met, in this case. The question, should we radiate, and if so, how should we radiate? So the first question, should we radiate? You know, there’s a nice study out of MD Anderson by Anita Mahajan and her colleagues that looked at the question in someone with a resected brain metastasis – does radiating the cavity help? And it certainly did when it came to the likelihood that the tumor would grow back. And that’s certainly one reason to strongly consider radiation.

The thing with brain surgery is that it’s a little different than having a mastectomy, for example, because, you know, their surrounding tissue is so vital that it’s often difficult, or even not recommended, to remove everything in one piece with a margin of normal tissue around, because you’d be removing normal brain which nobody would recommend.

As a result, you know, there’s often little cells left over at the cavity rim, even if you can’t see them on a scan. And that probably amounts to about a 60 or 70% chance that a tumor will come back at that site, if you don’t radiate. If you do radiate, it lowers significantly, but this is where “how should you radiate” comes about.

You know, historically we’ve used whole-brain radiation, even with one cavity. The data tells us we shouldn’t really do that anymore based on a couple of really great studies that were published a few years ago. But then the question comes about: should we use SRS like one day of radiation, or should we be a little bit more broad with our fields and use like five days of radiation or three days of radiation. But we don’t have to give an enormous amount in a single day. We can be a little bit more generous with our volumes and we can, you know, ideally, prevent recurrence in a safe way. Because essentially what the data has told us, as long as we hit the right target, the recurrence rates are pretty low, but when people have looked at SRS, the recurrence rates seem to be pretty significant.

So, really the answer that we’re going to get to this question, SRS versus SRT, one day versus more than one day, will come from an ongoing Alliance randomized study which is occurring very well, and that’ll compare SRS versus SRT to cavities, and I think that will be enormously impactful for them.

One thing to factor in, Lianne, and I’ll share the screen again, is when we do cavity radiation, I think it’s important to recognize that a lot of the recurrence risk is along the lining of the brain. And I think this is where we want to be pretty generous with the radiation fields.

So this is an example of a cavity and you can see the cavity in green. And you can see there’s no white area around it. There’s no contrast happening. But, you can see these other nodules that develop afterwards and they’re circled in red. And this is a tumor that’s occurring along the lining of the brain. And this is something that we think complicates surgery about eight or ten or twelve percent of cases, at least with a single institution series. That number can vary based on a number of factors. But when we design our radiation fields, we really want generous coverage of that lining of the brain to try to minimize the likelihood that the tumor’s coming back at that area that’s greatest risk.

Now, that example that I showed you, trying to include all that in a preemptive radiation field is too much, but I think the point is that we want a generous margin along the line of radiation.

Lianne Kraemer:

And I just want to clarify that when you talk about the cavity, that image was showing where a tumor used to be. When you say cavity, you’re saying that there used to be a brain metastasis there that you have removed. And so, what is left is referred to as the cavity.

Dr. Aizer:

That’s exactly right. So there used to be a brain metastasis here. There’s not, it’s just a cavity. And that’s a perfect description of it.

Lianne Kraemer:

So I wanna move on to side effects, but because we know that with radiation, it doesn’t come without some side effects. So let’s start with SRS and the side effects that you see, both immediately following SRS, and anything down the line, long-term, that you might see as a side effect.

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah, that’s a great point. So I’m going to try to focus, Lianne, on the side effects that are most relevant, because I think you can always go down a laundry list of what could happen, and that’s what we definitely do when patients consent to radiation. But I want to focus this on what actually really matters.

Like, not temporary side effects that’ll go away, or side effects that are not of great impact to the patient. But focus more on the side effects that could really impact how someone does on a day-to-day basis. So I always think of a couple of side effects in the short-term and then one side effect in the long-term, but it can manifest in different ways.

So in the short-term, the side effects are seizures and bleeding. Those are thankfully very rare. It’s hard to quantify that risk, but it’s probably about one percent. We sometimes use preventative seizure meds for like a week, to minimize that risk. Some people use shorter or longer courses. That’s all reasonable.

Some people don’t use it at all – that’s also reasonable because there are certain areas of the brain that can’t really generate seizures. So if a given patient’s doctor didn’t recommend seizure meds, that can be totally fine. The other risk is bleeding, and thankfully that’s also about a 1% risk in terms of a meaningful bleeding – one that the patient will know is happening.

And you know, typically we don’t see that very much in breast cancer. We see that more in tumors that are prone to bleeding, like melanoma or thyroid cancer or some ovarian cancers, as well as kidney cancer. And we still look at things like platelets and are people on blood thinners, but for the most part, that risk is also really quite low, thankfully with breast cancer.

The overwhelming long-term risk is something called radiation necrosis and it’s hard to quantify the risk of that because everybody has a slightly different definition of what that is. But what it basically means is that there is some inflammation and/or injury to the part of the brain that was treated with radiation.

And the first thing that can happen, and, I’ll share the screen one more time. The first thing that can happen, that we may not know that it’s radiation necrosis right away. Cause radiation necrosis can sometimes mimic the tumor. At least initially. So one thing that can come up is, you know, someone has, something that grew in an area that there was a tumor, for example, this is a patient who had a tumor here in the right parietal lobe, had radiation, and on the next grid there, now the top center image, that responded beautifully to radiation, but what you can see over time is that there was this increasing, fluffy, cloudy, enhancement, the whiteness, around the tumor. And this was radiation necrosis, meaning there’s no tumor there anymore, it’s all radiation injury.

You know, when we looked at this in another example, this is a patient who had this tumor treated and over a long time, it grew and then it grew more. And when you look at the bottom row, you see this other white stuff, which is swelling. So this is a sequence called a flare that’s just swelling really well.

And this can impact patients because it’s not just an area that is taking up contrast. It’s all of the swelling that can accommodate, and that can go along for the ride. So, you know, this can basically cause symptoms that are general in nature, like headaches or seizures, or it can relate to the specific area of the brain that was injured.

And this is a process that goes on for a while. It eventually will stop in the vast majority of patients. It might get a little better over time, but this is like a chronic process. It almost becomes a chronic disease. And this is one of the reasons that when we think about, you know, SRS to large numbers of tumors, and this is an example of a case where we did, you know, SRS to total about a total of 60 tumors, over three sessions, pink, blue and dark blue. You know, this is a fair amount of radiation given to the brain and some of these things, as you can see, have a decent amount of bulk to it. So this is probably the side effect that concerns us most about focused radiation. It is manageable, there are things we can do about it, but it does become a chronic disease that needs a lot of attention and even treatment options aren’t always perfect.

Lianne Kraemer:

Is there something that increases or makes the occurrence of radiation necrosis more likely – like the size of the tumor – or is there anything that makes someone more likely to develop this?

Dr. Aizer:

You’re spot on, Lianne, so the size of the tumor is an important consideration. Bigger size means more likelihood, no question about that. Prior radiation to the same area. So if this area has been radiated before, that will increase the risk of radiation necrosis. And then, other things like drug therapy given at the same time of radiation probably plays somewhat of a role.

Immunotherapy is increasingly relevant in cancer and in the breast cancer world. Some of the triple negative patients, and maybe some of the other patients who aren’t triple negative are getting immunotherapy. Sometimes standard, sometimes in the context of a trial. And we do think that that probably increases the risk of radiation necrosis to some extent. And so, you know, there’s a number of factors, but really size prior radiation and then maybe a third one is what drugs are they receiving, you know, play into that.

Lianne Kraemer:

Well and usually when you’re getting radiation, aren’t those drugs being held for that reason? Aren’t you told to stop your treatment, or something like that?

Dr. Aizer:

You make a really good point and we do often hold treatment for that reason. But there are some treatments that just can’t really be held. For example, immunotherapy is a good example. The half-life of most immune drugs is several weeks. So the idea of waiting three half-lives before you radiate the brain, doesn’t always seem viable.

The other notion is that sometimes it’s immunotherapy after the radiation that can be just as impactful as the immunotherapy that preceded the radiation. So, you know, yes, we try to hold when we can. Sometimes it’s just not possible or viable.

Lianne Kraemer:

So, how do you differentiate on a scan what is actually tumor necrosis versus what is a tumor – like the regrowth of the tumor or the failure of the tumor to respond to the radiation? Is there a test? Is there a way to know the difference?

Dr. Aizer:

Another great question, Lianne. So, you know, the gold standard is to take that area out. And then you’ll know under the microscope what it is. However, we don’t want to do that every time something grows after radiation because a lot of the times they’ll be removing radiation change that otherwise would have stopped anyway. And it may be before the patient even became symptomatic. Like you can see it on the scan, and sometimes it just stops growing. In fact, most of the time it stops growing before the patient even knows that it’s there. So, you know, to go and remove it preventatively, is sort of overkill for most patients.

There are advanced imaging tests that can be used. None of them are perfect and they’re all better than a coin flip. Are they a physician’s best guess, you know, based on other factors – hard to know. But tests like dual phase PET, MRI spectroscopy, MRI perfusion, we’re doing a study looking at the treatment response assessment map, which looks at the clearance of contrast over time and making an inference as to what that represents.

As promising as these tests are, they do have their limitations and they’ve been evaluated to different degrees. A lot of the times you can make sense of it based on the MRI. Initially, we really don’t know what’s going on, but over time, they’ll fork in the road, so to speak, there’ll be a classic necrosis appearance, there’ll be a tumor appearance, and most tumors, most areas will separate along those.

Sometimes it’s difficult to tell, and sometimes it can be a mix – like you can have both tumor and necrosis in the picture. So it really varies from person to person, but this is a really, really common problem in a brain radiation oncology clinic because we just see it everyday. .

Lianne Kraemer:

Yeah. So it sounds like it’s a really hard thing to delineate on a scan what the difference is. Is there anything happening with research that’s trying to look at this problem and solve this for patients. Cause, you know, obviously it’s really difficult if you can’t tell the difference between, or aren’t sure, exactly what is happening and the option to surgically remove the area to look at it doesn’t exist.

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah. That’s a great point, Lianne. So, you know, the best way to avoid radiation necrosis is to minimize the use of radiation, unless you feel like the benefit is better. A lot of times the benefit is there, but it’s important to think about that every time when you’re that patient. In addition, the technical elements of the radiation can be helpful in terms of minimizing risks. Trying to minimize the margins that are used, trying to do other things to try to keep the risk of radiation necrosis down. Holding drug therapy, as you astutely mentioned, can be helpful. You know, on the diagnostic side, as I touched on, there are some increasingly utilized diagnostic tests that can try to make this delineation noninvasively, but not are really perfect at this point.

And on the treatment side, you know, there’s a number of treatments for necrosis. There’s steroids, there’s a drug called Avastin which has been explored in breast cancer before, for example. And there are other treatments like hyperbaric oxygen and different drugs. But, ultimately, it becomes challenging. And I think, hopefully avoiding the problem in the first place is the best way to prevent it from manifesting, but a lot of the time you don’t have that choice. And thankfully we haven’t talked about those incidents, and thankfully this is more rare than common.

So we spent a lot of time talking about necrosis. On average 5, 10 or 15% of our patients will get necrosis when we radiate in a focused manner. So this isn’t something that happens 80% of the time. This is something that happens relatively infrequently on a per metastasis basis. And a lot of that 5, 10, 15%, people are asymptomatic. So, you know, I don’t want to overblow the problem, but at the same time, this is probably one of the most significant drawbacks of stereotactic radiation, especially when given to large numbers of tumors or both tumors.

Lianne Kraemer:

Yeah. I mean, when it’s a problem, it’s definitely a big problem. So even though that’s great to hear the risk of it occurring – the percentage – isn’t as high as maybe we think it is, but when it does happen, it’s definitely problematic. What about whole brain radiation? Is there a risk of necrosis with whole brain radiation?

Dr. Aizer:

It’s extremely rare. You know, it’s been reported, we’ve seen a few cases of it, but it’s exceedingly rare. If something grows after only whole brain radiation, meaning there was no SRS, no SRT given, that it really should be thought of as tumor growth, unless proven otherwise.

Again, we have seen over many, many, many cases in the denominator, a handful of necrosis cases with only whole brain radiation, but they are quite, quite rare. Whole brain radiation has its own side effects, so to keep it on the areas that are most relevant. In the short term, there is a lot of fatigue that goes along with whole brain radiation. It can happen with stereotactic radiation too, but you know, typically when smaller numbers of targets are radiated, it’s not as big of an issue.

So fatigue is a big one. That fatigue can last for a few months or sometimes longer. Appetite is a problem that can also be impaired for a few months, sometimes longer. And sadly hair loss, not in a focused manner, but a whole head of hair, can happen with whole brain radiation

When hippocampal sparing techniques are used, sometimes the hair loss is more gentle or some people actually don’t get much hair loss, which is an interesting byproduct of the hippocampal sparing that certainly a lot of patients appreciate it.

But, with conventional whole brain radiation and even some cases of hippocampal sparing, there is hair loss and that takes typically months to come back. The hair may be different when it comes back. It may not be as thick, or as vibrant, it may be curly where it once was straight, it may be brown where it once was different colors. So that’s another thing to factor in.

Long-term, I think the side effects I think about are the cognition that we talked about. And unfortunately, the long-term side effects are more permanent in nature, so cognitive problems, people’s balance can take a hit with whole brain radiation. And we see a lot of people who don’t have impeccable balance after that treatment.

And then sometimes there could be some hearing loss. But usually, that’s not a major effect. So, you know, those are the three short-term and three long-term side effects that I think matter most. You know, fatigue, appetite loss, hair loss in the short-term. Cognitive problems, balance problems and hearing loss, to some extent, in the long-term.

Not everything happens in every patient. A lot of our patients don’t get much of that at all, but those happen commonly enough that they, you know, impact a fair number of patients. So unlike stereotactic radiation where we’re talking 1%, 5%, 10%, with whole brain radiation, many of these things can happen – it’s just to what extent. And that’s certainly an issue to consider.

Lianne Kraemer:

I want to go back to hair loss because with, you know, women that’s, you know, that’s a really important thing. And being able to anticipate what is going to happen with your hair before you have radiation and knowing what to expect, I think is really helpful for women. So, you know, you talked a little bit about with whole brain radiation, in general, you’re going to lose all of your hair, I think you might’ve mentioned. What about in SRS?

Dr. Aizer:

SRS really varies a lot and it really comes down to this in surface dose, and just factors that are random from person to person – some people get side effects that others don’t. But typically a larger tumor near the skin surface, maybe along where the brain touches the bone of the skull, more likely to cause some hair loss. Something deeper, less likely to cause hair loss.

We mention it to all of our patients, cause you never really know. But it tends to be more of a factor of the tumors that are closer to the skin surface. It tends to be patchy though. So, you know, unless a lot of tumors are treated and the beams are coming in and out from many, many different directions, it tends to be areas that are smaller. You can cover it up more readily depending on hairstyles. So it tends to be a less significant problem. Still an important one, but a less significant one and one that often resolves more quickly, as well.

Lianne Kraemer:

How long does it take for the hair to start to regrow? Is there a period of time where you expect that hair to start to regrow in both SRS and whole brain?

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah, you make a good point. And the first thing is how long does it take to fall out? Cause people, you know, they finish radiation and the hair’s intact, and then it’s like, oh, maybe they won’t get it. But you know, the hair loss won’t start typically for 2, 3, 4 weeks after we do the first treatment. It’s a somewhat delayed effect.

So, you know, all of our patients finish SRG with the same hair that they had when they started five days prior. And certainly for SRS, that’s a hundred percent true – it’s just a one-day treatment. But then the question also comes about, how long does it take to grow back? And this varies in terms of like, which treatment was given. Whole brain radiation tends to be a little longer. Stereotactic is really variable depending on what the skin actually got.

But typically, sometimes we tell patients, 8 weeks, 10 weeks, 12 weeks, you might start to see something coming back and, you know, it varies from person to person. Some people get it back at 6 weeks. Some people, it takes 4 or 5 months. Everyone’s a little different.

Lianne Kraemer:

And then with whole brain radiation, well women, you know, who’ve had chemotherapy and they’ve lost all their hair, and when it starts to regrow, it generally regrows all at the same time. Like your hair comes in, you know, in your forehead and the whole scalp at the sort of the same rate, just like, as if you’ve shaved it, it might be really slow. But I think it’s a bit different, or more patchy with whole brain radiation. Is that true?

Dr. Aizer:

That is definitely the truth. It depends on how the whole brain radiation was given. Is it hippocampal sparing, is it not? Was there scalp sparing, was there not? What metrics were trying to be achieved on the radiation plan versus not? But yes, that’s classically with whole brain radiation, you know, you sometimes had a dose distribution that led to most dose kind of right at the top with it, where there’s the thinnest amount of tissue for the radiation to pass through. And that means that this is the area here, that the radiation, you know, this is the area that the hair loss comes. This is the area where the hair regrows last. So people would have hair coming back in other parts, but the top center, and in the middle, the hair is not coming back very well. So the reality is it really depends on how the radiation was done to know what to expect. Thankfully, with hippocampal sparing, you know, the hair loss does appear to be more gentle in nature, than with non-hippocampal sparing techniques.

There have been some metrics published, from Anand Mahadevan, has done a beautiful job. You know, a number of years ago, reporting in a small subset of his patients that were getting this technique initially, that they were actually keeping all of their hair and he reported his metrics. We’ve tried to emulate those metrics. Not a perfect system, but you know, the actual dose that the skin is getting and the scalp is getting, plays a big role.

Lianne Kraemer:

Yeah, I was just thinking, you know, obviously I’ve had radiation a couple of times. I haven’t had whole brain radiation. I know something that comes up in discussion a lot is the use of steroids. Steroids can be a really challenging drug to be on. As far as – do you have to use steroids in stereotactic radiation versus whole brain? What are the indications for use of it? When can it be avoided so that patients don’t have to use it? Can it be avoided?

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah, it’s a great question. And it’s going to vary a lot based on a number of factors. I think the first factor is does the patient need steroids even before they go into radiation? And do they have neurologic symptoms, or not? And if patients don’t, then the question becomes, do you want to add steroids? Increasingly, we are not utilizing steroids.

So for example, in my practice, and this is not right or wrong, I never preventatively give steroids. If patients develop symptoms that warrant steroids, then we’ll give them steroids. But in an effort to minimize the side effects that patients go through, I try to avoid steroids. Increasingly –

Lianne Kraemer:

Is that both SRS and whole brain that you’re trying to avoid using steroids?

Dr. Aizer:

SRS and whole brain. That’s right. Increasingly in the immunotherapy route, we’re even more concerned about giving steroids out of concern that steroids will blunt the effect of immunotherapy. The process of giving steroids can make immunotherapy not work.

Lianne Kraemer:

Now I want to ask you a question that is common amongst, our community, is driving, and how radiation affects, you know, the ability to drive. Can you drive after you receive radiation?

Dr. Aizer:

This is another tricky issue and there’s no right answer. I think in general, for a given patient, it’s not going to be a one size fits all situation. I think it’s important to talk to your doctor or your team. Whoever is on your team, it could be a PA or a nurse practitioner, or a nurse, or anyone who you feel like you feel comfortable to ask guidance on this issue from.

But the concern with driving in patients with brain tumors, including those who have radiation, are a couple of fold. One is that either the tumor itself or the treatments can impair someone’s ability to act accordingly. For example, if there’s a tumor in an area that’s controlling the right foot, and most of us use our right foot to go from gas to break, that inherently poses a challenge, whether you’ve radiated or not.

The other factor is seizures, and we worry that our patients with brain tumors can develop seizures. Thankfully most do not, the vast majority do not. When we’ve looked at this in our data, you know, if patients, about 10% of our patients with brain metastasis will have a seizure at diagnosis. And then if they don’t, about 10% will develop one thereafter. So taken another way, the majority of people will never develop a seizure. So I don’t want people to think that they’re prone to get a seizure, that’s not the intention. But the concern is that, what if someone’s behind the wheel, and all of a sudden, they, you know, are not aware of the surroundings, or they lose consciousness and that can be a significant issue.

So radiation, especially when given in a stereotactic manner carries some risk of seizures. It’s small. The estimates are not well listed. But it’s probably on the order of a low single digit percent. 1%, 2%, 3%, something like that. Some centers give preventative seizure meds with radiation to prevent that seizure for a short period of time.

But I think most of us would acknowledge that around the time people are getting SRS or SRT, we probably shouldn’t be – they probably shouldn’t be driving because of that small risk of this. In people who are getting whole brain, sometimes you just don’t feel up to driving. Like if the patient is tired or nauseous or, you know, is just feeling sluggish, it just may not be the right time to drive. So in general, around the time people are getting brain directed radiation, for brain metastasis, we generally advise not to drive. And, you know, thereafter, it really depends on the individual circumstances. And again, this ends up getting sort of into a discussion.

Lianne Kraemer:

Once you have finished radiation, whether it’s whole brain, or it’s SRS, what is the timeframe to when you do an MRI, to look at what the radiation did?

Dr. Aizer:

So, Lianne, that’s a great question. And there’s a number of factors to consider. So, I think if people are following guideline-based care, such as NCCN guidelines, you know, a consideration would be to do a repeat brain MRI in about three months after whole brain, or potentially two months after stereotactic radiation, with the shorter time interval for stereotactic radiation, being out of concern for the development of new brain metastasis. But, I think, you know, doctors and nurses and patients and therapists, and other people who manage brain metastasis, often recognize that one patient is so different from another.

So you have patients that have rapidly progressive brain metastasis, and they’re not going to jive with a two or three month follow-up. They may need a one month follow-up. You have patients who’ve had a long track record of having smoldering brain metastasis, meaning things barely changed with time. And even if we end up using radiation, we might not do the next scan for four months after because we really understand the trajectory of the disease and what we would expect.

So, it varies a lot from patient to patient and there are other factors to consider as well. But I think the most, kind of, standard would be about a couple of months after stereotactic radiation – you know, about two, or maybe, three months after radiation.

Lianne Kraemer:

Gotcha. I think that sticks with the theme of brain metastasis – that it depends. That seems to be the overarching theme that connects all answers about treatment and radiation – is it really is an individual thing. Is there any problem to screening too soon?

Dr. Aizer:

Doing a scan a little bit too early?

Lianne Kraemer:

Yeah.

Dr. Aizer:

So it’s a great question. And, you know, largely the answer is no. You know, there are some costs potentially to patients in the system. There’s the inconvenience of the scan. In patients with kidney function is it optimal, or if they have stage three, four, or five of the disease, the contrast that we use with the MRI, the gadolinium poses some risk, not a lot of risk, but a small amount of risk.

And then a recent discovery is that some of this contrast isn’t being entirely cleared by the body, in patients. But the ramifications of what does that actually mean on a day-to-day level remain highly unclear. So we have not been telling patients that they should refrain from scans for any of those reasons. If they have, for example, really poor kidney function, we will maybe do a scan without gadolinium. But, you know, largely, apart from those minor issues, doing a scan too soon, usually there’s not a lot of downside.

Lianne Kraemer:

Okay. So when you’ve completed radiation and you do the scan, what are you looking for? What is the goal of radiation therapy? What are you hoping to see? Is there something that you hope to see on the scan?

Dr. Aizer:

You know, it’s another really helpful point to talk about. And radiation is different than drug-based therapy in terms of what we expect to see in the scan. I think with most drug-based therapy whether it’s chemo or targeted therapy or HER2 directed therapy, hormonal therapy, you generally would assume that when things shrink it’s optimal and when things grow, it’s not. With radiation, it doesn’t really work that way all the time.

Initially, we can see some growth after radiation, just due to irritation of the tumor, by the radiation. So if we did a scan in a given patient five days after we finished radiation, oftentimes things would be larger. And that’s one of the reasons we don’t scan that early.

The other factor is that a lot of tumors will remain controlled, even if we can see them on a scan after they’ve been radiated. Because what we’re seeing on the scan may not be viable tumor anymore. It could be dead cells or cells that are non-functional, or there could be, you know, radiation induced changes that are mimicking what the tumor used to look like. So after radiation, scan interpretation is tricky and it does require a lot of thought and expertise and a team effort to try to interpret some of these scans because one of the most classic things that happens is that we do SRS or SRT for a patient and then a year later, things are larger and we’re trying to delineate – is this tumor growth, is this a late radiation tumor enlargement, called radiation necrosis.

And these are difficult to delineate. And as a result, you know, it’s the type of thing where, you know, now that reports are immediately accessible to patients, that’s wonderful in many ways, but it also can be problematic for some patients, because they’ll read “enlargement of this site” in a given part of the brain. And I think the immediate conclusion that some patients make is that the tumor’s growing, when in reality, that may not be the case a lot of the time.

Lianne Kraemer:

So it’s really important to talk to your oncologist, your radiation oncologist, about what your particular results mean. And it sounds like, over time, it may vary in what you’re saying. When you say controlled you’re meaning that there’s not growth. Am I correct?

Dr. Aizer:

That’s right.

Lianne Kraemer:

Okay. So it isn’t necessarily an expectation that your scan needs to show shrinkage and then complete disappearance of the tumors in order to indicate that you’ve had success with radiation.

Dr. Aizer:

That is entirely true.

Lianne Kraemer:

Okay. I think that’s an expectation we see a lot with those in the breast cancer, brain mets community, is expecting that those tumors will completely disappear. And when they don’t, it can be confusing.

Lianne Kraemer:

So let’s move on to research. Is there anything happening right now in the field of research for radiation and brain mets that would be helpful to know about?

Dr. Aizer:

Yeah, there’s a lot going on, and I think, ultimately, this is a good thing for patients. And you know, there’s different types of questions being asked and, you know, at a higher level, there are questions being asked – who needs radiation and who doesn’t, which types of patients may be managed with drugs alone versus with radiation. And this extends a little bit beyond breast cancer, sometimes, because each drug and each type of cancer has its own drugs, some of which will work, some of which may not, in the brain specifically. So the questions kind of vary from disease site to disease site. But that’s certainly an ongoing issue.

And then, there’s a lot of questions focused on how do we make radiation either more effective in patients who need it to be more effective, or less toxic, if the radiation has a track record of yielding some side effects. Some examples would include, you know, ongoing studies trying to delineate who really can get away with stereotactic radiation, SRS, or SRT. Whole brain radiation there are multiple ongoing studies of that kind. There are studies looking at using radiation with a radiosensitizer – so a drug designed to make the radiation work better. We have a study open at our center on that front where we have patients who have historic, or tumors that have historically not displayed the greatest control range with radiation, and they can receive a radiosensitizer in some of these studies that ideally makes the radiation work better, but doesn’t impart some of the toxicities that might be seen if we just increased the dose, for example. None of this has been definitively established, but that’s why it’s done in the context of the study.

I think there’s a lot of interest, on a separate note, patients who need surgery for a brain metastasis and this comes up in breast cancer a fair amount because of the historical lack of screening MRIs. In patients who need surgery, when we give radiation after surgery, based on the way it’s been done in studies, which is a single day to an entire cavity, the results have not been as ideal as we would have hoped. More people are recurring in the cavity than we would have expected. The surgery can propagate tumor cells beyond the cavity and that radiation can’t account for that anymore. And then there can be necrosis because they’re often radiating a generous size area with a single day of high dose radiation.

So there have been a number of studies looking at fractionating radiation, like breaking it up into multiple doses. And those are ongoing currently. And a really exciting concept is doing the radiation pre-op. So, giving the radiation and then taking the patient into surgery, with the idea that you’re treating their tumor and even if the surgery, you know, disperses some of those tumor cells, they’ve been treated by the radiation and hopefully, are less likely to propagate elsewhere because essentially they’re non viable. This is a paradigm that’s used in other cancers and the question is can we apply it in brain mets.

So there are other exciting concepts as well. There’s drug plus radiation concepts… ability of radiation and drugs to work together to manage a given patient. And, thankfully, there’s more and more studies being conducted each year. But I do want to emphasize that in brain metastases, we do lag behind other cancer entities with similar incidents.

So if you look at the number of brain metastasis per year, it’s roughly the same as the number of breast cancer diagnoses per year, or colorectal cancer diagnoses per year, lung cancer diagnoses per year or prostate cancer diagnoses each year in the United States. But when you look at research output, whether you measure that in terms of active clinical trials, completed trials, abstracts presented at major conferences, we lag behind in this field.

So as much as is being done to promote the health and wellbeing of patients with brain metastasis, there is an even bigger need to do more. So I think this is where we need, you know, patients, nurses, doctors, funding agencies, companies, coming together to try to dedicate studies to patients with brain metastasis.

Lianne Kraemer:

That’s a really interesting point that you make. Do you have any kind of thoughts on why that is?

Dr. Aizer:

Well, you know, I think there’s a number of factors to think about. The field has gotten better in many ways, but historically, not only did we have not have a lot of trials for patients with brain metastasis, but if patients had brain metastasis, they weren’t even eligible to get a drug designed to look at the effect in the body.

And thankfully, we see the transition from that, to allowing those patients to be on study if they get the tumor treated beforehand. To now, what’s really exciting is studies testing whether a drug can work in the brain among patients with active brain metastasis. And I think that’s come a long way forward. But, historically, I think, funding agencies and companies are a little reticent to put patients on their studies because of the concern that the brain would progress while the body remains controlled. And that might not reflect well on a given drug or may prematurely terminate a drug from development that otherwise was promising.

So I think that’s been a historical issue. I think, in the past there hasn’t been as much attention given in the literature to the unique nature of brain metastases. They’re different than liver metastasis or bone metastasis and lung metastasis, they have inherent challenges and issues associated with them. And I think increasingly we’re seeing more awareness. We’re seeing things like dedicated meetings for brain metastasis patients. A few years ago, SNO had, for example – that’s the Society for Neuro Oncology – had the first dedicated meeting for specifically brain metastasis. And that was a huge success.

There are other brain metastasis meetings that are upcoming. For example, this year there’ll be the first conference dedicated to clinical trials relating to brain tumors which is sponsored by ASCO/SNO and a lot of those studies include brain mets-specific studies, so I think that’s exciting. And so I think the future is bright, but we definitely have a long way to go in terms of promoting research in this population.

Lianne Kraemer:

I agree. We do. I wanted you to jump back to one of the studies that you mentioned, just out of curiosity, about reversing when the radiation occurs and that now you typically do the radiation after surgery occurs, and then you discuss that research is looking at doing radiation before surgery. Why would you need to do surgery if you have gone ahead and radiated the tumor? Isn’t that just like getting SRS and waiting for it to shrink?

Dr. Aizer:

That’s a great question. And so you – this would come up if you’ve made a determination that the patient needs surgery. And typically you’ve made that determination based on – the most common scenario is a larger tumor that’s causing a bunch of symptoms and that steroids have not yielded good enough effect for.

So you’ve made the determination that the patient needs surgery and then the current standard is to get the radiation after. Here, what you are going to say is, okay, we understand that. We understand that the radiation is probably not a good long-term strategy by itself because it’s a little bit more difficult to control a bigger, bulkier tumor. You’re giving less dose. These often behave more poorly than smaller tumors. And, you know, ultimately the patient may have symptoms that aren’t going to get better anytime soon if it’s just radiation alone. If it’s surgery then it can quickly be compressed. So you’ve made that determination the patient needs surgery and then now you’re adding that, you know, preoperative radiation. But you make a really good point – you could say like, why not? And that would typically be for the patient who just doesn’t quite need surgery yet, you know?

Lianne Kraemer:

Makes sense. Yeah, thank you for that clarification.